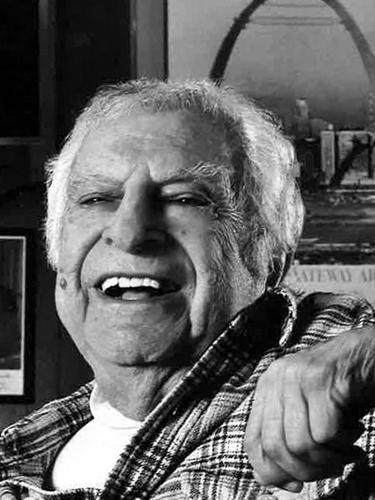

Woody Zenfell, came to St. Louis in 1960 to become the government engineer in charge of building the Gateway Arch. And, he was the Executive Director of the St. Louis Council of Construction Consumers from 1973 to 1993.

None of the skilled workers on the massive Arch project were African-American. That brought demonstrations followed by a government decision that the Arch wouldn’t be built without blacks.

But, at the time, there were no skilled black crafts workers to do the work. The construction trade unions that controlled training for jobs had refused to admit blacks as members. It looked like the Arch wouldn’t get built.

Mr. Zenfell was a white man from Mississippi who, by his own account, was reared without any apparent sympathy for the civil rights movement.

Mr. Zenfell was a career public servant. He was an engineer for the National Park Service who worked in Mississippi, Maryland, Tennessee, Virginia and North Carolina. In 1960, he was offered the job of chief engineer in charge of taking the Arch design and building it.

He kept a sign on his cluttered desk bearing the title “park engineer.”

A project like the Arch, he worried, “had never been done before, and a lot of people said it couldn’t be done.”

He was almost right, but not because of any engineering issues.

The local chapter of CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) charged that blacks could only get jobs as common laborers on the Arch project and the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial at its base.

In July 1964, Percy Green and Richard “Dick” Daly climbed 125 feet up one leg of the 630-foot Arch. They stayed there, drawing international attention to the lack of black workers.

Mr. Zenfell had to coax them down.

President Lyndon Johnson got involved with an executive order, and the government forced the prime contractor to hire minority subcontractors and black skilled mechanics.

Mr. Zenfell said his work in fighting for equal rights might do more than delay the Arch project. “It might never be finished,” he said at the time.

The International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 1 had no African-American members when Mr. Zenfell started. He got the union to open its doors, first to 20 black journeymen and 12 apprentices.

After his work on the Arch, Mr. Zenfell joined the U.S. Labor Department as a senior official in charge of contract compliance. He went on to help break racial barriers in East St. Louis, Kansas City, Des Moines and across the country.

Mr. Zenfell grew up in Vicksburg and Clarksdale, Miss., where his Lebanese immigrant parents operated a general store. He earned an engineering degree at Mississippi State University before joining the Park Service. During World War II, he was a lieutenant in the Navy on cruisers in the Pacific.

Mr. Zenfell said that while he had come to St. Louis to build the Arch, he “didn’t just want this to be a structure of stainless steel.”

Just as important, he said in a meeting with Mayor Alfonso Cervantes, was ensuring that justice was done to ensure the rights of everyone involved with building the Arch.