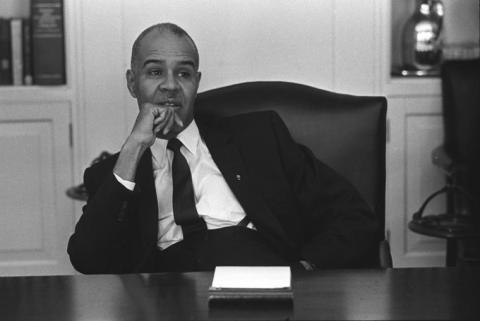

ROY WILKINS, Executive Director, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)

Roy Ottoway Wilkins (August 30, 1901 – September 8, 1981) was a prominent activist in the Civil Rights Movement in the United States from the 1930s to the 1970s. Wilkins’ most notable role was his leadership of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), in which he held the title of Executive Secretary from 1955 to 1963 and Executive Director from 1964 to 1977. Wilkins was a central figure in many notable marches of the civil rights movement. He made valuable contributions in the world of African-American literature, and his voice was used to further the efforts in the fight for equality. Wilkins’ pursuit of social justice also touched the lives of veterans and active service members, through his awards and recognition of exemplary military personnel.

Wilkins was born in St. Louis, Missouri, on August 30, 1901. His father was not present for his birth, having fled the town in fear of being lynched after he refused demands to step away and yield the sidewalk to a white man. When he was four years old, his mother died from tuberculosis, and Wilkins and his siblings were then raised by an aunt and uncle in the Rondo neighborhood of Saint Paul, Minnesota, where they attended local schools. Wilkins graduated from Mechanic Arts High School.His nephew was Roger Wilkins. Wilkins graduated from the University of Minnesota with a degree in sociology in 1923. In 1929, he married social worker Aminda “Minnie” Badeau; the couple had no children of their own, but they raised the two children of Hazel Wilkins-Colton, a writer from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Introduced at the August 1963 March on Washington as “the acknowledged champion of civil rights in America,” Roy Wilkins headed the oldest and largest of the civil rights organizations. The NAACP, founded in 1909, aimed to achieve by peaceful and lawful means equal rights for all Americans. Since the 1930s, it had focused its resources on challenging “Jim Crow” statutes in the courts, winning the landmark decision in Brown v. Topeka Board of Education in 1954, the first major crack in the wall of segregation. By the early 1960s, with a new generation of activists trying a more confrontational approach, Roy Wilkins remained a moderate but insistent voice for progressive action, with a direct line to the White House.

View digital copies of his correspondence with the White House:

Letter (1/24/61) from Roy Wilkins to JFK after attending the President’s inauguration.

Letter (4/5/61; pages 16-19 in this folder) from Roy Wilkins to Harris Wofford, President Kennedy’s Special Assistant for Civil Rights, with a critique of the administration’s civil rights record

Telegram (6/22/61) from Roy Wilkins to the President reacting to appointment of federal judge in Mississippi.

Letter (8/3/61; pages 77-79 in this folder) from Roy Wilkins to JFK during the Berlin crisis regarding “the fact that in a goodly number of states the National Guard is closed to Negro citizens” and urging that “appropriate steps be taken without delay to insure the inclusion, on a non-discriminatory basis, of all citizens in all aspects of the spiritual and physical mobilization you have ordered.”

Telegram (12/14/61) from Roy Wilkins to the President, urging him to issue executive order banning racial discrimination in federally assisted housing.

Telegram (12/28/61) from Roy Wilkins to the President on the postponement of executive order on discrimination in housing.

Telegram (7/30/62; pages 78-79 in this folder) from Roy Wilkins to the President urging him “To speak out in condemnation of the persecution in Albany, George, of Reverend Doctor Martin Luther King and his associates for peacefully protesting racial injustices.”

Letter (3/18/63; pages 59-61 in this folder) from Roy Wilkins to JFK regarding racial discrimination around the area of Cape Canaveral, Florida: “There is a particular irony when the soaring aspirations exemplified in the United States government’s programs for probing the far reaches of space are contrasted with the harsh reality faced by Negroes who are contributing to those programs…”

Letter (5/15/63; pages 135-137 in this folder) from Roy Wilkins to JFK regarding Prince Edward County, Virginia, where public schools had been closed since 1959 to avoid complying with desegregation orders following the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education.

His confrontation of the Jim Crow Laws led to his activist work, and in 1931 he moved to New York City as assistant NAACP secretary under Walter Francis White. When W. E. B. Du Bois left the organization in 1934, Wilkins replaced him as editor of The Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP. From 1949 to 1950, Wilkins chaired the National Emergency Civil Rights Mobilization, which comprised more than 100 local and national groups.

He served as an adviser to the War Department during World War II.

In 1950, Wilkins—along with A. Philip Randolph, founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and Arnold Aronson, a leader of the National Jewish Community Relations Advisory Council—founded the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights (LCCR). LCCR has become the premier civil rights coalition, and has coordinated the national legislative campaign on behalf of every major civil rights law since 1957.

Roy Wilkins as the Executive Secretary of the NAACP in 1963

In 1955, Wilkins was chosen to be the executive secretary of the NAACP and in 1964, he became its executive director. He had developed an excellent reputation as a spokesperson for the Civil Rights Movement. One of his first actions was to provide support to civil rights activists in Mississippi who were being subjected to a “credit squeeze” by members of the White Citizens Councils.

Wilkins backed a proposal suggested by T. R. M. Howard of Mound Bayou, Mississippi, who headed the Regional Council of Negro Leadership, a leading civil rights organization in the state. Under the plan, black businesses and voluntary associations shifted their accounts to the black-owned Tri-State Bnk of Memphis, Tennessee. By the end of 1955, about $300,000 had been deposited in Tri-State for that purpose. The money enabled Tri-State to extend loans to credit-worthy blacks who were denied loans by white banks. Wilkins participated in the March on Washington (August 1963), which he had helped organize. The march was dedicated to the idea of protesting through acts of nonviolence in which Wilkins was a firm believer.[9] Wilkins also participated in the Selma to Montgomery marches (1965) and the March Against Fear (1966).

He believed in achieving reform by legislative means, testified before many Congressional hearings, and conferred with Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, Ford, and Carter. Those achievements gained Wilkins attention from government officials and other established politicians, earning him respect as well as the nickname, “Mr. Civil Rights”. Wilkins strongly opposed militancy in the movement for civil rights as represented by the “black power” movement because of his support for nonviolence. He was a strong critic of racism in any form regardless of its creed, color, or political motivation, and he also declared that violence and racial separation of blacks and whites were not the answer. As late as 1962, Wilkins criticized the direct action methods of the Freedom Riders, but changed his stance after the Birmingham campaign, and was arrested for leading a picketing protest in 1963.

On issues of segregation, as well, he was a proponent of systematic integration instead of radical desegregation. In a 1964 interview with Robert Penn Warren for the book Who Speaks for the Negro?, Wilkins declared, We Negroes want the improvements in the public school system – and among them, of course, the elimination of segregation, based upon race – the institution of the same quality education in the schools attended by our children as those attended by other children, and we want Negro teachers and we want Negro supervisors, and we want all the opportunity, but the only way our form of government and our structure of society can survive is by some common indoctrination of our citizenry, and we have found this in the public school system. And, for any reformer, black or white, zealot or not, to come along and say, “I’ll destroy it, if it doesn’t do like I want it to do,” is very dangerous business, as far as I’m concerned.

However, his moderate views increasingly brought him into conflict with younger, more militant black activists who saw him as an “Uncle Tom.”

Wilkins was also a member of Omega Psi Phi, a fraternity with a civil rights focus and one of the intercollegiate Greek-letter fraternities established for African Americans.

In 1968, Wilkins also served as chair of the U.S. delegation to the International Conference on Human Rights. After turning 70 in 1971, he faced increased calls to step down as NAACP chief.[14]

In 1977, at the age of 76, Wilkins finally retired from the NAACP and was succeeded by Benjamin Hooks.[4] Wilkins was honored with the title Director Emeritus of the NAACP in the same year.[2] He died on September 8, 1981, in New York City, from heart problems related to a pacemaker implanted on him in 1979 because of his irregular heartbeat.[2] In 1982, his autobiography, Standing Fast: The Autobiography of Roy Wilkins, was published posthumously.

“The players in this drama of frustration and indignity are not commas or semicolons in a legislative thesis; they are people, human beings, citizens of the United States of America.”

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roy_Wilkins

https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/education/students/leaders-in-the-struggle-for-civil-rights/roy-wilkins